Articles

Avant-Jazz: Japan’s Unique Era of Jazz During the 1970’s.

For Japan’s music history, the 1970’s was such an important period. It grew the country’s international audience and exposed a great deal of individuality in a once isolated culture. This article only touches on a handful of essential listening from this era of jazz. I don’t doubt there are plenty of understated gems out there that were once wrongly overlooked.

Japan’s Growth Out of a Historically Insular Culture

Japan has a long history of limited exposure to the outside world, in particular during the Edo Period between 1603 and 1867 under the Sakoku; a policy in which trade and relations with other counties were severed almost entirely. Until the 1850’s, few people entered or left Japan during this time.

With the end of the Isolationist policy in 1853, Japan began to rebuild its relations with other countries and their cultures - in particular with western powers. By the 1920’s, Japan was in its most liberal phase yet. The country saw not only an early emergence of avant-garde art and culture, but also its first jazz musicians. It is said that jazz found its way to Japan via visiting Filipino bands who had picked up this style of music from their American occupiers.

However, relations with the United States began to sour in the wake of the Pacific War. The “Americanness” of jazz music in Japan became increasingly controversial, and by the start of WWII the music was banned. Nonetheless Its popularity remained, and by the late 1950’s Jazz had had a great revival.

Japan also became the world’s second largest economy (after the United States), it’s rapid growth taking place predominantly in the 1960’s. With this, an avant-garde movement resurfaced, and contemporary Japanese art, music and culture gained a far wider global reach. Artists now had boundless access to draw inspiration from external cultures.

Meanwhile, jazz was becoming a more and more abstract music in the west, recognised as a method instead of defined as a genre. Artists were being increasingly innovative with their playing, in part as a by-product of audiences turning their focus to rock and other growing genres. Initially, Japanese Jazz held a reputation for being an imitation of the U.S scene, therefore was relatively disregarded by both American and Japanese critics alike. However Japan’s jazz revival, in particular from the late 60’s-mid 80’s, was in fact host to an outburst of experimental and creative musicians.

Free Jazz, Funk-Fusion and Spiritual

A defining figure in the development of Japan’s free jazz scene is pianist and composer Toshiko Akiyoshi. Renown pianist Oscar Peterson came across Akiyoshi on tour in Japan in 1952, who then promoted her to his producer Norman Granz. Akiyoshi released ‘Toshiko’s Piano’ with Granz in 1954 - the beginning of her success in both the U.S and Japan. Akiyoshi is regarded as the first artist to break away from American imitation and demonstrate individuality in Japan’s jazz scene. By the 1970’s, her sound incorporated traditional Japanese instruments and styles making her music more of a spiritual jazz.

Akiyoshi was a pioneer in the veering away from ‘jazz for dance halls’, which dominated as the popular style of music. For some musicians there was a degree of anti-establishment in their playing; after historic periods of contained culture, being experimental was not always hugely respected. Therefore independent record labels such as Three Blind Mice played an important role in showcasing emerging jazz artists and favouring unique talent. One of their more renown artists being Isao Suzuki, who once again can be heard incorporating a Japanese style of playing into his jazz.

Three Blind Mice recordings were also high quality. Japanese recording studios were stand out at the time; during their economic boom, much of the music equipment used globally was designed and manufactured in Japan, both technologies and musical instruments. Which meant the records coming out of Japan during the 1970’s are still to this day some the highest quality jazz records ever recorded. This was something I actually noticed before I learnt about Japan’s economic revival, listening to Jiro Inagaki & Soul Media’s epic funk-fusion album Funky Stuff. The recording is incredibly clean and the sound is well balanced; even the gentlest dynamics are unmistakable. I double took when I saw the album was released in 1975 - it was album that led me to research Japan’s jazz of the 1970’s.

Another unique display of jazz-fusion is Hiromasa Suzuki’s High-Flying, an album that largely draws on funk and prog-rock, characterised by groove-heavy synths and electric guitar solos. This has got to be my favourite funk-jazz album from this era.

An album that is a picture of free-jazz, funk-fusion and spiritual jazz is Unicorn, by Teruo Nakamura. Released in 1973, this experimental album contains wild drum breaks, fast moving baselines and high energy solos from all instruments.

Amidst the vastly expressive free-jazz and synthy fusion sounds, The 1970’s also elevated some of Japan’s most respected “classic-style” jazz musicians. Trumpeter Fumio Nanri was one. Nanri obtained a name for himself, coined by Louis Armstrong himself, as the ‘Satchmo of Japan’, and was one of the earliest of Japan’s jazz musicians to gain international recognition. This recognition spanned from the 1950’s up to his death in 1975, aged 64. A year prior to his death, Nanri released his final record, named Farewell, just a year prior to his death. His playing was incredibly skilled and beautifully gentle, always in a Dixieland style. Have a Listen to ‘It’s the Talk of the Town.’

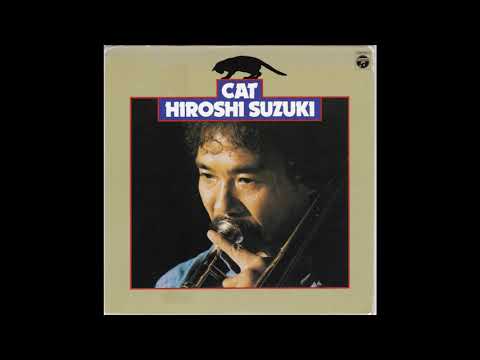

Trombonist Hiroshi Suzuki was another essential musician in the scene, who was very late to be recognised. His 1975 album Cat was recorded in Japan after Suzuki had lived in Las Vegas for 4 years. It was overlooked by critics at the time of its release, perhaps for being “not fusion enough” and having somewhat simplistic sound. However Cat has had plenty of recognition in later years. In 2015 Columbia Records rereleased the album, although the demand for this record was prominent long before. The final track Romance has been sampled countless times, by the likes J Cole on his remix of Can I Kick It by A Tribe Called Quest, or by Vanilla on Fuji, amongst many others.

By Willow Cunningham, 05.04.2022

References:

Attack Magazine; How Japanese Technology Shaped Dance Music. 2022: https://www.attackmagazine.com/features/long-read/how-japanese-technology-shaped-dance-music/

Crépon, Pierre; Omnidirectional Projection: Teruto Soejima and Japanese Free Jazz. Tatsuro Minami, 2019: https://pointofdeparture.org/PoD67/PoD67Japan.html

Bischoff, Björn; Hiroshi Suzuki: The Unknown with the Trombone. HHV Magazine, 27.06.2021: https://www.hhv-mag.com/en/feature/11691/hiroshi-suzuki-the-unknown-with-the-trombone

Johnson, Brandon; Hiroshi Suzuki’s “Romance” is in Love with Modern Music. The Gleaming Sword, 01.08.2020:https://medium.com/the-gleaming-sword/hiroshi-suzukis-romance-is-in-love-with-modern-music-e17310a3628

Marshall, Colin; A 30-Minute Introduction to Japanese Jazz from the 1970s: Like Japanese Whisky, It’s Underrated, But Very High Quality. Open Culture, 10.04.2020: https://www.openculture.com/2020/04/a-30-minute-introduction-to-japanese-jazz-from-the-1970s.html

Nations, Kate; The Sabukaru Guide To 1970’S Japanese Jazz. Sabukaru Online: https://sabukaru.online/articles/sabukaru-guide-to-1970s-japanese-jazz

Rothberg, Emma; Toshiko Akiyoshi. National Women’s History Museum, 2022: https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/toshiko-akiyoshi

Takao, Ogawa; A Mosaic of Music: Jazz Pianist, Composer, and Arranger Akiyoshi Toshiko. Nippon Communications Foundation, 2019: https://www.nippon.com/en/features/c03708/

Van Nguyen, Dean; ‘Society was volatile. That spirit was in our music’: how Japan created its own jazz. The Guardian, 12.01.2022: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2022/jan/12/how-japan-created-its-own-jazz